The 1914 Ingram-Foster Biplane

Learn more about the 1914 Ingram-Foster Biplane.

The Ingram-Foster biplane is believed to be the finest surviving example of an original Curtiss-design pusher. It was designed after the first biplanes flown in New Mexico by Charles Walsh in 1911, and Lincoln Beachey in 1912. To commemorate these landmark flights, The Albuquerque Museum and the Albuquerque International Sunport jointly purchased this historic airplane for the people of Albuquerque. Its presence in the Sunport is a monument to the history of early aviation in New Mexico.

In contrast to modern aircraft, the propeller is located in back of the craft and it pushed, rather than pulled, the biplane through the air. Most of the airplane, including the wing fabric, is in original, unrestored condition. Minor repairs have been made to the wing fabric and bamboo since the plane was acquired in 1987. Only a very small number of parts, including some of the rigging wires, have been replaced.

A Biplane Biography

While on a business trip to Dallas, Jay Ingram, a Ford dealer from Decatur, Texas, met Charles A. Foster, an exhibition flier who used the stage name Lavivian. Foster's flying stories sparked Ingram's imagination, and the two men struck a deal. Foster would come to Decatur, build aeroplanes, and together they would form the Pioneer Aeroplane Exhibition Company. Ingram gave Foster complete access to his automobile shop, and provided $2500 for the purchase of a six-cylinder Roberts engine.

In six months, Foster built a copy of a Curtiss pusher that was sturdy enough for limited aerobatics. The wheels, tires and many fittings were purchased from mail order aeroplane supply houses. The ribs, interplane struts and wing sections were custom-made from raw lumber. The wings were covered with cotton or linen fabric and painted with a varnish made from cellulose dissolved in ether. The 100 horsepower, two-cycle engine burned a 20:1 ratio of gasoline and castor oil.

After a series of successful test flights, Foster and Ingram built four additional biplanes. Between 1914 and 1916 they contracted with county fairs in Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas to stage exhibition flights. As aeroplanes became more common, however, the Pioneer Aeroplane Exhibition Company received fewer contracts. By 1916, only one airworthy Ingram/Foster biplane remained. Jay Ingram packed the surviving biplane, spare parts and tools in their original traveling crates and stored them, where they remained untouched for 70 years.

In 1968, John Bowden of Lampasas, Texas, a pilot and airplane restorer, learned of the aircraft and offered to purchase it from Jay Ingram's descendents. The family agreed to sell the plane to Bowden in 1986. Bowden purchased the biplane essentially sight unseen, as it was stored in a building too cramped to open the crates.

After moving the crates to Lampasas, Bowden found the airplane to be intact and remarkably preserved. Except for the white rubber tires, which required restoration, the plane was in original condition. He painstakingly reassembled it, and was even able to restart the Roberts engine. In 1987, Bowden sold the plane to The Albuquerque Museum and City of Albuquerque Aviation Department.

Aeroplanes!

In the years following the Wright Brothers' first flight in 1903, several companies were formed to stage aeroplane exhibition flights at fairs and amusement parks. The stars of these shows were dashing young aviators, or “fliers.” Many would-be fliers built planes from plans published in popular magazines. Learning to fly was often a matter of taking an airplane to the nearest pasture, starting the engine, and making a series of successively longer hops.

Glen Curtiss won the Scientific American silver trophy and $2,500 for the first officially witnessed flight of over one kilometer (.62 mile) in the United States.

- 1910

Eugene Ely became the first aviator to successfully take off from the deck of a ship. The next year he made a successful landing on the deck of a ship, demonstrating the feasibility of aircraft carriers. - 1911

Lincoln Beachey became the first to successfully fly upside down. - 1911

Lincoln Beachey set an altitude record of 11,642 feet. - 1913

Lincoln Beachey became the first American pilot to loop an airplane.

The First Aeroplane Flight in New Mexico: Charles Walsh

In the years preceding the 1911 New Mexico Territorial Fair, attendance at the territorial fairs became so poor that funds had to be raised to cover operating deficits. Agricultural displays, baseball games and horse racing were no longer attracting large crowds. The Fair Association desperately needed an act that would boost attendance, and they decided that an air show would fill the bill.

Fair Association chairman P.F. McCanna contacted the renowned Curtiss Exhibition Company of Hammondsport, New York. Glenn Curtiss agreed to send aviator Charles Walsh and a Curtiss pusher biplane to New Mexico. The contract stipulated that Walsh would make two flights for $200.

Charlie Walsh had flown for less than a year before his Albuquerque appearance. He had built his first airplane, a copy of a Curtiss pusher, in the yard of his California home in 1910. Walsh was a conservative pilot. Rather than performing stunts, he preferred to take passengers on short hops to demonstrate the practical uses of the aeroplane. He also filled small bags with flour and bombed targets on the ground to illustrate the military potential of aircraft.

Walsh's exhibition plane was a Curtiss Model biplane powered by a 75 horsepower eight-cylinder engine. It was shipped to Albuquerque by rail and assembled at the Territorial Fairgrounds west of Old Town by a crew of mechanics.

The Albuquerque Morning Journal described Walsh's first flight of Oct. 11, 1911:

The first flight was made at 4:10 [p.m.] when the aviator started his engine, glided his wheels half way across the baseball diamond and rose gracefully into the air. Reaching a considerable height (about 1,000 feet above ground), he struck southward and followed the river down as far as the Barelas Bridge, circling around until he was above the railroad tracks, coming northwest across Robinson Park. Passing again in sight of the packed grandstand, which cheered him ecstatically, Walsh then repeated his trip, being in the air altogether ten minutes before he swept over the trees on the east side of the fairgrounds and alighted like a feather on the diamond, miscalculating his speed just enough to stop in a puddle of water west of the ball ground. Even at that it was a most wonderful demonstration of control, as Walsh had previously announced that he would alight just where the wheels first struck the ground.

After landing in front of a cheering crowd, Walsh made a second flight of 13 minutes. On Oct. 12 he made two longer flights, ascending higher and traveling farther than his flights of Oct. 11. City officials thanked Walsh for notifying local hospitals and sanitariums so that their patients could watch him circle around those institutions.

Walsh also carried the first passengers to fly over Albuquerque. On the final day of the fair, Ray Stamm climbed aboard for a three-mile flight at 200 feet above the city. Stamm described the experience:

I seated myself on the seat arranged on the lower plane [wing] just at one side of the engine and we started. Rising from the ground you simply feel yourself floating up into the air and it is hard to tell at what minute the machine leaves the ground.

Walsh was surprised by the agile performance of the heavily laden airplane at Albuquerque's elevation of almost 5,000 feet. The next day he took two more passengers on similar flights. He ended his 1911 Albuquerque activities with three high altitude flights, eventually reaching 8,000 feet.

Stunt Flying: Lincoln Beachey

For the 1912 New Mexico Territorial Fair Charles Walsh was replaced by Lincoln Beachey, the best-known exhibition flyer in America. Beachey was the undisputed master of the Curtiss Model pusher biplane. Two months before his Albuquerque flights, he set an altitude record of 11,642 feet above sea level in a Curtiss pusher. He earned as much as $4,000 per week stunt flying and competing in automobile-versus-airplane races against drivers like Eddie Rickenbacker and Barney Oldfield.

Beachey's stunts amazed Albuquerque residents. His dangerous antics and close flybys had injured and even killed spectators in other states. Albuquerque newspapers called Beachey a foolhardy daredevil. During baseball games held on the racetrack infield, he flew over the diamond and buzzed the players, causing many to drop to the ground or scatter. He then gained altitude and took his hands off the controls to wave at the crowd. He ended each performance with his famous death dive:

Rising to a height of 1,500 feet [above the ground] he started a spiral glide and then shutting off his motor, he pointed his machine straight downward and made a sensational drop of probably a thousand feet. Suddenly he righted the biplane and glided to a perfect landing within the Fairgrounds.

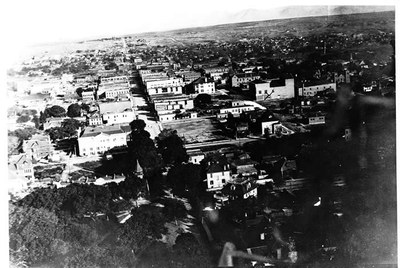

Beachey's role as the number one attraction at the fair was short-lived. The second day of the fair he struck a fence and damaged his plane. The remainder of his contract was fulfilled by aviator Roy Francis, whose flights of 1913 produced the first aerial photographs of Albuquerque.

How to Crate a Half-ton Aeroplane

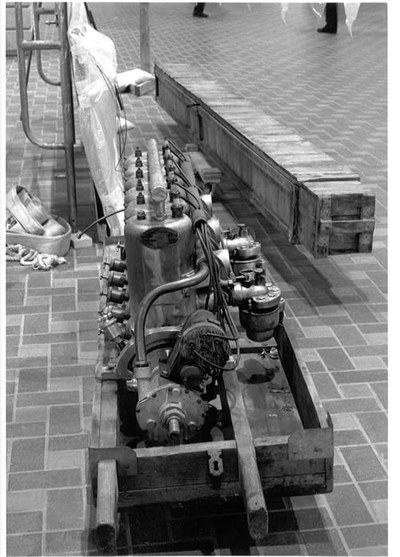

The 1914 Ingram/Foster biplane traveled on railroad flatcars to county fairs in Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas between 1914 and 1916. Railway shipment was preferred; otherwise, the pilot would have to land the craft every 200 miles or so to refuel. The plane “rode the rails” in four large crates made of pine, cross-braced for support, and painted in festive colors of blue and red. No other similar crates are known to exist.

The largest crate contained the wing sections. A smaller crate, angled at the top with a metal lid, held the airframe (chassis). The engine was bolted into the framework of a flat crate with a tall lid; handles allowed the loaders to gently handle this heavy but delicate load. Finally, a narrow, long crate held extra parts and tools.

The 340-pound Roberts engine was secured with four long bolts to the inside of the crate, which was constructed with handles so the load could be hand-carried. The long crate was used for storing extra front wheel braces, wing struts, and other long parts and tools.

Acknowledgments

The following companies, foundations and individuals generously assisted staff of The Albuquerque Museum and the Albuquerque International Airport with the 1989 documentation, conservation and installation of the 1914 Ingram/Foster Biplane:

For their help towards the 1989 installation of the biplane, our appreciation is expressed to the members of “New Mexico is Taking Off:”

The following organizations, businesses, and governmental agencies contributed their time and resources to the 2001 conservation of the biplane and renovation of the exhibit: